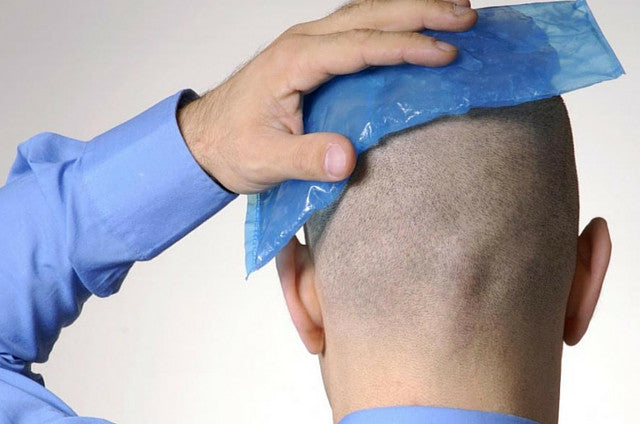

When we bump our heads, sprain an ankle, or are suffering from tendinitis, the answer is always the same:

“Ice it!”

“Three times a day!"

“It’s important to ice it to get the swelling and inflammation down."

Icing is part and parcel of being an athlete: Go to any sporting event—from a local track and field competition to the CrossFit Games—and you’ll find athletes sitting with multiple ice packs to numb their pain, and pumping Advil to ready their bodies for their next event.

Is it possible, though, that most health professionals we’ve come across throughout our lives—may have led us astray?

Dr. Braham Jam, a physiotherapist, thinks so. He argues that not only is icing not necessary much of the time, it might even be counterproductive as it slows long-term healing.

Why do we ice anyway?

1. Ice to reduce pain

One of the main reasons we ice injuries, bumps and bruises is to prevent, or at least reduce pain. We achieve this by restricting blood flow to the area, which helps numb the pain.

2. Ice to reduce inflammation and swelling

A second reason to ice is to reduce inflammation and swelling. But in a paper published by the Advanced Physical Therapy Institute (APTEI) in April, 2015, Dr. Jam explained the belief that inflammation and swelling should be minimized is exclusive to the western culture.

3. Ice to reduce cell death after an acute injury

Icing decreases tissue temperature, which is believed to decrease cell metabolism, which limits hemorrhage and cell death after an acute injury.

Why we might have gotten it wrong?

In his APTEI paper, Jam explained there isn’t actually a lot of research to support our arguably blind love for icing. In other words, science hasn't been able to show icing helps that much, especially when it comes to overuse injuries.

“There’s a moderately-sized collection of controlled experiments on using icing (or “cryotherapy” as it’s known in medical circles) for acute injuries, like ankle sprains and post-surgery recovery, but research into icing for overuse injuries, like the ones runners get, is quite limited,” he said. “In fact clinical trials on the efficacy of RICE (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) have supported the use of compression but have found no value in icing…”.

Jam added: “You mean to tell me after all these decades we don’t yet have a single study to support the use of ice with respect to enhancing tissue healing and hastening recovery? Could it be that the use of ice has been a hoax? We have all been somehow duped to believe that ice is so effective that it did not even require scientific scrutiny and supportive evidence?"

Not only is Jam suspicious ice might not be that helpful, he suggests icing might even be counterproductive to healing.

His rationale is this:

Inflammation is the body’s natural response to an injury, so why are we trying to stop it artificially?

“Inflammation is an inevitable and an essential biological response following acute soft tissue injuries. It is a protective attempt by the body to remove the damaging stimuli and to begin the healing process,” Jam said.

Contrary to popular opinion, Jam believes the same is true of swelling.

“The buildup of fluid, swelling or edema at the site should be considered a positive reaction as it increases sensitivity to pain (to prevent us from further injuring the tissue), restricts movement (to prevent us from further injuring the tissue) and allows the inflammatory process to progress (to help us repair the injured tissue),” Jam wrote.

So while icing an injury might help in the short term by eliminating pain and swelling, over the long term, it “may be negatively affecting tissue remodeling,” Jam explained. In other words, ice prevents the injury from healing the way it should, making you more susceptible to re-injury, Jam explained.

Is Jam Alone?

Jam isn’t alone in his thinking.

Gary Reinl, who has spent more than 40 years in the sports medicine industry, is another who questions the value of icing injuries. Reinl feels so strongly about the subject he wrote a book called, “Iced! The Illusionary Treatment Option.”

Similarly, recent articles, such as this 2014 Macleans article, “Why ice doesn’t help an injury and could even make it worse,” provides evidence that also suggests icing isn’t the solution we thought it was. The article points to a 2013 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, which suggests icing might even delay recovery from eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage. Further, a Runner’s Connect article, “Stop Icing Your Running Injuries" paints a similar picture.

Should you give up your ice before 16.4?

Probably not.

If your priority is to be as pain free as possible for 16.4 in three days, chances are you’re going to employ a short-term healing plan, including ice, tape, and pumping painkillers—basically whatever you can do to maximize your chances of reducing pain and competing well.

Jake Joachim, the head athletic trainer for the Vancouver Whitecaps, was quoted in the 2014 Maclean's article, explaining that even though there is limited evidence about the effectiveness of ice, when it comes to elite athletes, he continues to promote it:

“If there’s a tremendous amount of swelling, my No. 1 thing is to return function. Part of returning function is getting that swelling out,” Joachim said in the Maclean's article.

But if you’re not about to compete tomorrow if, for example, you’re on your off-season or you’re suffering from tendonitis that just won’t go away, and you’re interested in long-term healing, Jam’s perspective just might be worth considering.

Leave a comment: